My best friend since eight grade happens to be a middle school librarian, and whenever we get together, we eventually talk shop. She's got lots of great ideas about book titles and writing about books, and this summer when we were traveling together to celebrate a milestone birthday (we're two weeks apart in age), she mentioned a book they'd gotten in at their library called Getting Beyond Interesting: Teaching Students the Vocabulary of Appeal to Discuss Their Reading by Olga M. Nesi. While it's aimed more at middle school, I figured that I could use it in fifth grade, and boy, have I ever.

The first or second day of school, I had students do a writing response to a picture book I read. I gave them a few guidelines, but I really just needed a baseline sample for what kinds of writing they could do about their reading. Most wrote a couple of vague sentences, and none were in any way outstanding in their analysis. The day after, I started introducing the terms that Nesi uses in her book: tone, pace, characterization, and story line. I had the students write down a general definition of each in their reading notebooks for reference, and then I handed out a "bookmark"from Nesi's book with the different terms and some examples of each. For tone, students could choose from bittersweet, humorous, melancholy, etc... Pace included gentle, lively, or fast. Characterization included describing characters as believable and relatable, or quirky, among others. Story line asked students to think about whether the story was more action based or character based, and we discussed what that might look like in a story. As I read the day's story, students were given time to check off terms on their bookmarks that they thought fit the story we were reading.

After a group discussion of what they thought the story was in each category, we proceeded to write a short paragraph using these terms. What a difference having some language to use made in these paragraphs! Students were talking about why they thought the pace was gentle, or why the tone was bittersweet. Having some terms to use made them analyze their reading more closely and made their discussion more specific; instead of saying, "I really liked the book," now they were able to tell what it was about the book that made them like it.

Eventually, we moved to writing a paragraph about one of the terms, instead of all of them in one paragraph. This has allowed students to deepen their thinking, giving several examples to support their thinking rather than just one. Their final writing project this trimester is a literary essay, and for that, they will need to pick three of the four terms, write paragraphs to support their thinking, and include an introduction and conclusion. We have talked about what happens if you didn't like the book, and how you could say, for example, that the pace was slow, which did (or did not) fit the story, and that you don't like books with a slow pace because they don't capture your attention (or whatever your reason is). As the year goes on, I hope that the usage of the terms becomes more automatic, and that kids will be talking about them when they recommend books to one another. Having some vocabulary to discuss their thinking has really made a difference in my classroom this year.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Sunday, September 21, 2014

Word Art

One of the areas we know we need

to work on as a school is vocabulary. With a number of second language

speakers, this becomes even more important, and with the increasing academic

vocabulary as the students move up through the grade levels, knowing the

meanings of words is critical. While I love learning about words, this love isn’t always

shared by my students, and I’ve given a lot of thought to ways to make learning

new words more engaging, and not just a “drag out the dictionary and copy down

the meaning” exercise.

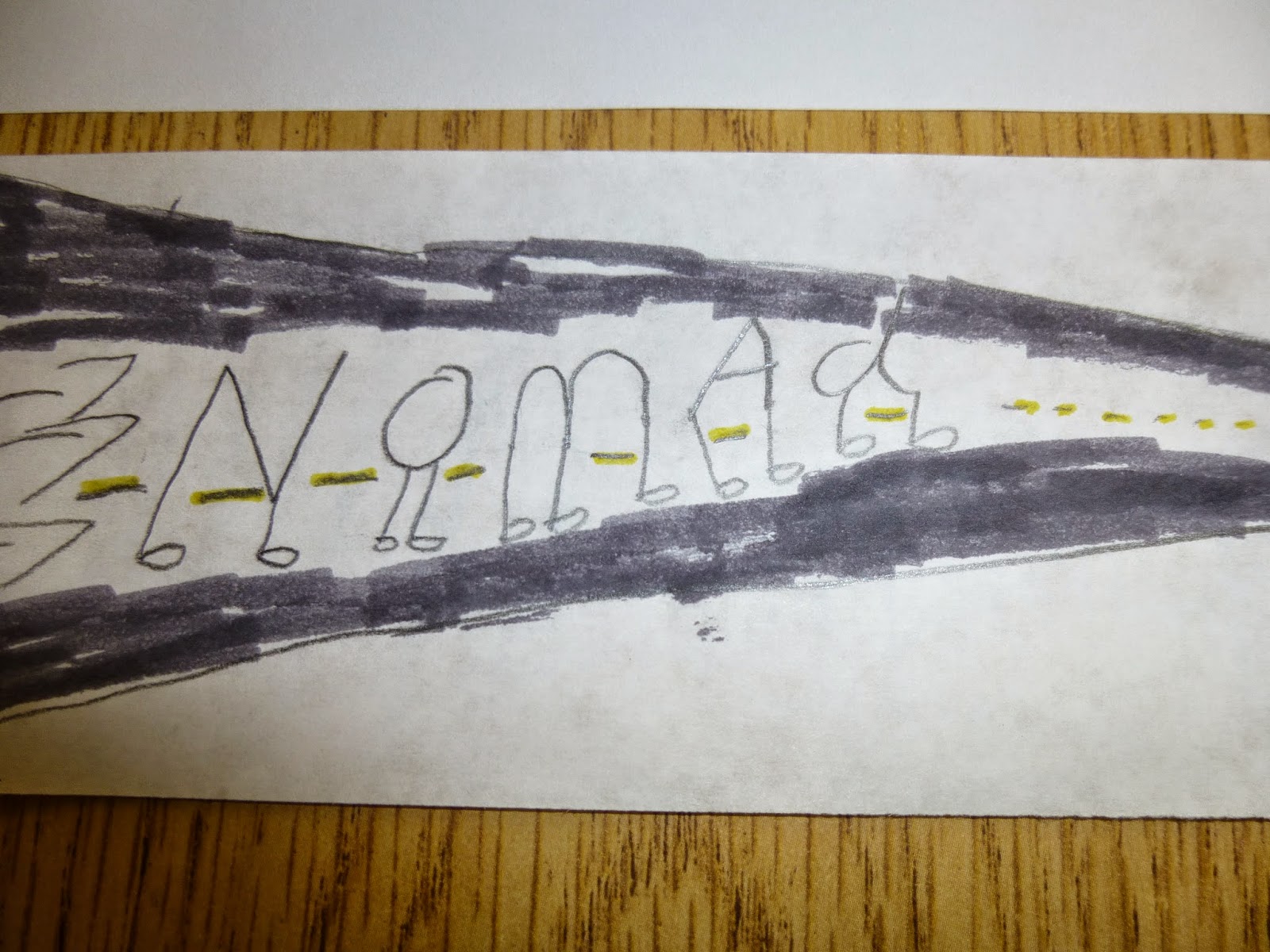

One thing I tried this week was “Word

Art”, another idea I got from the book Learning in the Fast Lane, by

Suzy Pepper Rollins. Kids take the

word and use it to draw something that represents the meaning of the word but

still incorporates the letters. I used the vocabulary words from our first

social studies unit on First Americans, and gave the kids a choice about which

word to illustrate. Many chose “migration”, and used the letters to show the

word “moving” across the paper. One student illustrated “nomad” by having all

the letters walking with feet. One of my Muslim students chose “stereotype” and

included a picture of a woman in a headscarf using the letter “o”. I think this

would be a fun activity to use in any subject area, and I plan to have it as an

independent activity during guided reading and intervention times. I posted

them on the wall so students will have a chance to see how others illustrated

each word, and also so the current unit’s vocabulary is on display while we are

in that unit. My colleague found a bunch of adding machine tape and we cut up

long strips for the kids to use, which they also enjoyed. I’d recommend this if

you’re looking for something a little different to do with vocabulary!

Saturday, September 13, 2014

Six-Word Memoirs

The school year has begun, and this year I’ve looped up to

fifth grade with my two groups of kids from last year. So far I have loved

coming back and just starting in – it seems like we just had a long weekend,

and we’re back at it. But one of my concerns was making sure that fifth grade

didn’t just feel like a repeat of fourth grade, so I knew I had to alter the

routine a bit, and start with something we didn’t do last year.

The May 2014 issue of The Reading Teacher featured an

article called “Every Word is on Trial: Six-Word Memoirs in the Classroom,” by

Jane M. Saunders and Emily E. Smith. Students work to come up with six words

that describe them or something they are interested in, and then find an image

to enhance their memoir. That sounded like something doable (six words isn’t

many), fun (computer lab), and it would be a great way to start and finish a

writing project the first week.

Following the suggestions in the

article, we first looked at Ernest Hemingway’s famous memoir, “For sale: baby

shoes, never worn.” It was a great

place to start, as we did a lot of inferencing about what he could have meant.

I then pulled up some examples on brainpickings.org of elementary six-word

memoirs (www.brainpickings.org/2013/01/09/six-word-memoirs-students), which

gave my students some ideas for their work. I was careful to stop at the middle

school level, as some of the examples are a little racier than I wanted to

share with my class. Then students

all worked to come up with several examples, discussing with classmates if they

were short a word or had too many. It was fun to see the discussions of how to

condense ideas, or how to change words around to get the best effect.

Punctuation also becomes important if you aren’t writing complete sentences, so

some students experimented with colons and commas.

After choosing the memoir they

liked best, we headed into the computer lab. The article gives many great

suggestions of how to present the memoirs, but in the end, I just had students

open up a Word document, and then we searched for images on Flickr as they did

in the article. Once an image was selected, students dragged them into the Word

document, and then typed the memoir below the image. We printed them off in

black and white, and then students had the option of using colored pencils to

make them more colorful.

I hung them all up outside our

room, and students have really enjoyed reading what others have written.

Several staff members have also commented on how nicely they turned out. One

colleague suggested doing this periodically throughout the year and using them

as a chronicle of fifth grade, which I really like. I also think students could

do this as a short way of synthesizing information from other subject areas. I’m

going to experiment with this writing form throughout the year and see what I

think. For now, it was a great way to start our new year off together.

Here is my example that I showed the students.

Saturday, June 14, 2014

Standards Walls

Standards Walls

Earlier this spring, a co-worker loaned me a new book called

Learning in the Fast Lane by Suzy Pepper Rollins (ASCD). It has a lot of good ideas for helping

all students succeed. One of the

suggestions was to create a standards wall. At our school, we’ve been encouraged to post learning

targets, which I dutifully did, but they’re in small font and there are so many

of them, that they were basically meaningless for both me and the students.

|

| Sorry - I can't figure out how to rotate this image! |

Rollins suggests posting the standards and learning targets

as a concept map up on the wall. As you move through the learning targets, an

arrow tracks your progress. Instead of standards written and posted where

nobody can see them, now everyone – both students and teachers – can see

exactly what you are learning, and where you’ve been, and where you still need

to go.

I decided to try this with our last social studies unit on

the West, and also for our narrative writing unit. I found it was very helpful

for social studies, because it really helped me tell the kids each day what our

learning target was, and then I could point out what we had already done and

where we were going. The narrative chart was helpful, but I found that in

teaching writing, there are often many things going on at once that kids need

to be aware of, and moving the arrow was less helpful. However, just having the

“I can” statements that go with the learning targets posted on a readable

poster was very helpful.

Rollins also suggests posting examples of student work by

the learning targets, and I did post my own examples of what we were working on

for the narrative unit. I liked being able to show kids who were absent what

the rest of the class had worked on, and showing examples always helps. I will

try to post more student work next year.

I’m definitely going to do this for social studies next

year, because those units change, but I’m thinking that I may be able to do one

concept map for reading and one for writing, since those subjects have a

different structure than social studies does. At any rate, having a big,

readable poster really helped me to chart our learning progress. And luckily, I

have all summer to try and plot out the standards walls for the fall.

Sunday, May 25, 2014

Revision: A Guest Post

Tom is one of my oldest professional colleagues. He's younger than me, so not that kind of old, but we've both been at the same school for over twenty years, making us some of the old timers now. For the last decade or so, he's been teaching mostly math, but when he's not doing that, he's writing. His writing career started at an early age, and he's been writing ever since. I knew this about him when I decided to take on the National Novel Writing Month challenge a few years back. I am going to take credit for convincing him to give it a try, and he has kept going with it, long after I quit. He knew he had some good stories to tell, and for the last couple of years, he's been pursuing finding an agent for one of his NaNoWriMo books. Happily, this is the year for him, as he signed with an agent who is excited about his middle grade book, FOLLOWING INFINITY. We decided to do guest posts on each other's blogs, and I asked him to share some thoughts on revision, which is a challenge for most of us, no matter what our writing ability.

Our district began specializing in intermediate grades ten years

ago, which means I haven’t formally taught anything to do with writing since

2004. There have been times I’ve missed working with a curricular area I’m so

passionate about, but when I read Betsy’s blog and learn of the strategies she

incorporates into her classroom, I’m reminded of what an uphill battle it can

be to engage elementary students in writing. Then it seems that maybe working

with numbers and shapes isn’t so bad after all.

In a post Betsy wrote about revision, she described how she had

students pair off to share their writing and offer each other suggestions about

how to improve their work. Too often the students would report back to her that

the writing was already good enough so no changes were necessary. Speaking as a

teacher, hearing a comment like this would have me mentally roll my eyes and

redirect the students to try digging a little deeper, and give them some

direction of what to look for. To hear this comment as a writer could quite

possibly drive me into pulling my hair out. To put it simply, a lot of what

people would think of as writing takes place in the revising. I’ve made the

comparison for people that drafting a manuscript is a lot like a sculptor

getting their hands on a massive lump of clay, and the revising that follows is

when that clay is gradually molded into art. To highlight my point I decided to

keep track of how many times I’ve made changes to this post you’re reading

before I decided it was ready to send to Betsy. Updating this paragraph will be

the last thing I edit before I send it, so I can now say I’ve read and revised

this post in some way at least twenty different times.

I thought it was great Betsy was trying to get her students to

work with critique partners, since that’s what many aspiring and professional

writers do. The trick is finding people who will understand what you’re trying

to accomplish, even if they don’t necessarily share your vision, and will be

able to read critically and provide you with honest feedback. I’ve been lucky

enough to have a small group of people over the years (Betsy being one of them)

I’ve been able to rely on as some of my first readers. Collecting opinions from

different people helps you identify any problems you might not see yourself

because you’re too close to the work. If you have a lot of people identify how

something about your story isn’t working for them, it’s pretty clear that needs

to be addressed. But sometimes you’ll get contradicting feedback and you have to

go with your gut on what to do. Example: Last summer a teacher friend read

through a middle grade manuscript I had just finished revising. She gave me

some great feedback, including points about one particular (and I’d say

pivotal) scene that left her feeling so disturbed she had to stop reading and

walk away from it for awhile. It made me wonder if I had pushed the moment too

far for the age group of the target audience. Fast forward to eight months

later when I received revision notes from my agent Carrie, who also had

comments on that same moment but in the opposite direction. Hearing from

different people, especially regarding a scene that could be polarizing, helped

me clarify why it was important to keep it; ‘disturbed’ was the reaction I had

been going for after all, and it worked. But without the benefit of outside

opinions to consider I may not have reflected on that scene the way I did, and

as a result I might have missed out on newer ideas that stemmed from that

moment.

I’ll admit, when the revision notes came in from my agent I

opened them with an equal mix of excitement and trepidation. We’d already

discussed an overview of her ideas during a couple of phone calls so I knew

what to expect. I was looking forward to seeing her specific notes and getting

back to work because I knew she understood what I was going for and saw ideas

to explore that would make the manuscript even better. But it meant a lot of

revising to do on a project I’d already done a fair amount of heavy lifting on

three or four times before. Her feedback wasn’t exactly “I love this so much,

now go back rewrite the whole thing,” but some of the changes she suggested

were big: edits that could result in removing entire chapters, developing

characters she wanted to see more of, cutting some characters out, redefining

the relationships between others, and expanding on sections of the story to

develop the overall progression. This was no thirty seconds of us standing in

the back of the classroom and then me telling Mrs. Quist that “my partner

thought it was good so I don’t really have to change anything.”

But if I hadn’t gotten that kind of feedback, I would have been

disappointed. For her to think about the manuscript so critically shows me how

invested she is in seeing this become something more. And I have to say, it

was both reassuring and a little scary to know just how dead-on her

suggestions were. With the work I’ve been able to do on it so far, I can

already see the new directions the story will go and what it will be like when

it’s finished.

And once it is, you can bet I’ll be anxious to hear Mrs. Quist’s

opinion.

If you would like to read more about Tom's writing life, plus a host of other topics (he has an extensive music collection, views a variety of movies, and is generally a reflective kind of guy), I recommend you check out his blog What I Did On My Summer Vacation. http://ernieyoureafool.blogspot.com

Saturday, May 17, 2014

On-line posters

Next year I’ll be doing something new: all of our fourth

grade teachers will be looping up to fifth grade, keeping our same classes that

we’ve had this year. I’m very excited about this for a number of reasons. I’ve

been in fourth grade for thirteen years, and I’m feeling like I need a

curriculum change, and I’m glad I’m moving up as I like the complexity of the

content as the grades move up. I’m also happy to be spending another year with

these kids; we’ve had a great group and I’m glad I can continue on with them.

That being said, I know that I need to mix things up a bit

for next year, and provide new opportunities for these students so that it

doesn’t seem like a complete repeat of fourth grade. One area I plan to have

kids use more often is technology in the classroom. They need to be able to comfortably word process a

page-length document by the end of fifth grade, and I know that much of their

work in middle school will be done and turned in on computers, so I want to be

sure that they’ve had opportunities to do that in my classroom before moving

on.

I also want to hit the ground running in the fall, since I

don’t have to take all the time to get to know them like I have all the other

years, and to that end, I’ve started to introduce some things that we can

practice now, and then hopefully just review a bit before putting it into

independent practice in September.

One project we’ve tried is making multi-media posters using

our district’s Discovery Education account. Each student has a user name and

password, and once they log on, they can begin to use some of the tools

Discovery Ed has. I had my students

make multi-media posters about the Dust Bowl, since we had just read a

nonfiction text in guided reading. Using the Board Builder program, students

were able to include text boxes, still photos, and maybe best of all, short

movies from the Discovery Ed collection, all to give the best information they

could about the Dust Bowl.

The posters are far from perfect, but the students were very

engaged each time they had a chance to work on them. They especially liked

selecting movies (no surprises there), and many included more than would be

ideal on their posters. It would be great to have them look at each other’s

posters and offer suggestions, and I may get to that this spring, but that

would be a definite skill to practice in the fall. They were also quick to pick up the basics, and helped each

other out, making it much easier for me to get around to help on more difficult

tasks. They could even access this account from home, and a few students did

that.

I’m including a couple of examples of posters below; there

could be all kinds of discussions about how effective or distracting the

backgrounds are, if there is enough information in the text boxes, and what

else is needed to make the poster more easily understood. But it’s a start for

now, and will definitely be an option for “showing what you know” in the fall.

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Exploring Text Structure

It’s been a while since I felt like I’ve done anything new,

but spring is kind of here, and with it comes restlessness that needs novelty.

I don’t know if this counts as novelty, but I’ve been excited by the thinking I’ve

seen the last couple of days in my classes.

Our latest reading unit is on text structure, which, for

some reason, I just couldn’t get my head around. I understand that it is how

text is organized, and that there seem to be more text structures in nonfiction

than fiction, at least for fourth graders, but I don’t think I could really see

why spending a lot of time with this topic made sense. In order to try and get

more out of this, I reread the structure chapters in Falling in Love with

Close Reading, and I decided to make a checklist for my students to use. I

took an opinion piece about school uniforms that students were supposed to

read, and copied that piece along with a structure checklist, and gave it to my

students. Then we proceeded to read the text together.

As we went through the piece, students could see that the

point of the writing was to convince the reader that school uniforms were

great. Then we continued to read, finding examples of claims, counterpoints,

and descriptions. Finding and naming what the writer was really doing in the

piece was interesting to me; I’ve done similar things in the past, but I liked

breaking down the structure even more specifically. Students color-coded the

different structures, underlining each in a different color, so that when we finished, it was clear that in this

opinion piece, the writer used claims more than any other structure to get his

point across.

The past couple of days, we’ve spent reading a book called Farm

Workers Unite, which tells about Cesar Chavez and his work starting the

United Farm Workers union. We did the same thing with the structure checklist,

reading the introduction, and then a chapter about the life of migrant workers.

For that chapter, I had the kids work together to “code” the text structures. I

then asked them to identify the structure used the most often, and to tell why

they thought they writer used that the most for that chapter. It didn’t take

long for the kids to notice that it was almost all cause and effect writing.

The hard part (but for me, the most interesting part) was thinking about why the author used that

structure. One student pointed out that it was very different from the introduction,

which led us to chat more about why that would be. I pointed back to the title of the book, and then a number of

kids got more animated. “The writer has to show how bad it was for the migrant

workers, so that he can explain why they decided to unite and go on strike.”

I’m not going to read every nonfiction piece with a

structure checklist nearby. But as an adult reader, it’s made me more conscious

of looking at how writers organize their writing. Now my goal is to be more

purposeful in helping kids see why writers choose the structures they use to

best communicate their thinking, and maybe it will transfer over to student

writing. It’s worth a shot!

Saturday, March 1, 2014

Communication

We’ve just finished up our

“spring” conferences (with our below zero temperatures and multiple feet of

snow, it doesn’t feel anything like spring), and I am part of a school team

that is working together to move our school to Title One status next year, and

both opportunities have left me thinking a lot about parent communication. It’s

clear that both as a teacher and a school, we have room for improvement.

It isn’t that I don’t communicate.

I do. In fact, I think I provide a fair amount of information about what is

going on in my classroom. I send home a newsletter (we started with biweekly,

but have moved to a monthly calendar, which my wonderful partner teacher also

emails to families with email accounts), and I update my website each week,

listing my homework requirements and providing links to copies of the homework,

in case a student has misplaced it. I let parents know about this in each

monthly newsletter, and I told each family about this at the fall conferences

in October. However, I still found myself telling families this same thing

again at our spring conferences, especially those families that said, "When I ask my child if they have homework, they always say no." Sorry to say, not all kids are reliable reporters, so I have my homework online.

Our school sends home a monthly

newsletter as well, but I’m pretty sure that like our monthly calendar, many

families don’t have time to read it. An additional concern is the language barrier that a number

of our families face; long sheets in English don’t help if you don’t speak or

read English.

So I’m trying to think of ways

that would be more effective in reaching more families without putting in

additional large amounts of time. Our school has a Facebook account, and a

number of families have “liked” that, but our principal pointed out that a

large number of the likes are from staff members. I think if we were to post

things more regularly on that page, we might find more people checking it out,

and I think our staff is interested in exploring that.

Another idea that we tried to

start using this fall is Remind 101, a very slick text message reminder system

that would have allowed us to send out text message reminders about homework

due dates, field trips, or special days at school. The teacher can set up

messages in advance on his/her computer or cell phone, set the time for them to

be delivered, and the parent then receives the message in a timely way. The parent

cannot send a reply back, so the teacher’s privacy with regards to his or her

own cell phone remains intact. I would have loved to use this but our district

has currently said no due to privacy concerns. It isn’t meant for emailing

individual concerns about students, but someone needs to convince our district

of that.

I’ve also read about a number of

classrooms in other districts using a class Twitter page to update families. I

think this would be fun, and I would train students to write something each day

and then they could type it up. I don’t know how many families are on Twitter,

but I’d be interested in exploring this further. At this point in time, I

believe our district has said no to this as well.

Finally, I need to find ways to

more effectively communicate with families who are not English speakers. I

think there are translating programs or tools online that I may investigate for written work,

and lately I’ve been thinking about writing up some kind of script and having

my students who speak that language be filmed saying the script in their native

language. I would then put it on my webpage and show all the students in my

classes, who could tell their families at home to watch it.

What are the best ways you’ve

found to communicate with families?

Sunday, February 9, 2014

Cleaning Cotton

We’ve had a crazy winter here in Minnesota, and have so far

missed five days due to cold, not snow.

It’s made getting back in the rhythm of school a bit challenging since

our winter break, and I’ve found that I’m feeling like I’m constantly behind

compared to where I was in my curriculum last year. I’m also disappointed that I haven’t been as

inspired to blog, since I don’t feel like I’ve tried anything worth blogging

about. But this week I did do an activity I discovered last year, and maybe

some of you will think it’s worth doing.

As a northerner, I haven’t seen a

field of cotton, let alone worked with it in any form other than cotton balls

from Target, so I was pretty interested. It comes with tons of seeds in it, and

also bits of leaves and stems. I had the students create a t-chart labeled “I

notice/I wonder”, gave them each a pile of cotton, and they got to work. I

loved hearing their conversations as they worked to get the seeds out, and I

had to remind them to put those good ideas down in writing so they wouldn’t

forget them! It’s one of the best activities I do in terms of engaging the

students, because everyone is busy trying to get those seeds out. After a while, someone usually says,

“Did the slaves have to clean the cotton like this?” It leads to some

realizations about the difficulty of the work slaves did, and is a great segue

into discussion of the cotton gin and how technology changed cotton farming.

Cotton Classroom also includes

Solomon Northup’s primary document about slaves picking cotton, and it’s a

great resource to help students realize how difficult and often violent the

life of a slave was. Once the students have spent some time trying to clean

that cotton, they are even more receptive to Northup’s descriptions of the work

expectations masters had of slaves. There is no good way to recreate the slave

experience, and I’m not sure I’d even want to try, but this small activity has

been a great way for students to begin thinking about slavery and technology. I

highly recommend it!

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Revising with a Peer

I am not the master of having kids review each other’s

written work. It isn’t that I haven’t tried it before. I have. Many times. And

it invariably goes something like this: “Class, I want you to get with another

person. I want them to read your story and offer suggestions about how to

improve it.” I try to model and give suggestions about how this might work, and

it always seems to go well when we do this as a class with something I’ve

written. But once they get with a peer, it takes about 30 seconds before both

students announce that they’re done. I’ll ask, “What changes did you make?”,

and the kids will say, “We didn’t need to make any. My partner thought what I wrote

was really good.” I will smile,

and cringe inwardly, because I know that changes could be made. Revision is challenging for good

writers, let alone ten year olds, and once something is down on paper, most of

us don’t want to change it.

Happily, I was visiting with one of my very dearest friends,

who is a teacher librarian at a middle school, and she teaches a writing

workshop for sixth graders. She

told me about having her students revise by having them ask each other

questions. “They need to ask the other person something that will allow the writer

to give more information,” she suggested.

I liked the sound of this because it was more concrete than

other revision directions I had tried. My teaching colleague tried this a week

before I did, and had really good results with kids writing short essay/opinion

paragraphs. I tried it with our Slice of Life writings. As soon as the draft

was done, they got together with a partner, and either read the slice, or had

it read to them. I wanted them to write their question on a post it note, so

that I could easily see what it was. I also wanted to see if the writer

incorporated the answer to the question in their revision. (We did this as a

class first before working in pairs.) The pieces I’ve seen so far showed much improvement over

their first draft, and the students seemed engaged and on task when they were

working with each other, so I’m encouraged by this effort. One of the things I

have to evaluate is whether they use the writing process, and making revisions

meets this goal.

I’m looking forward to trying this more as we write more

Slice of Life pieces and also begin working on our essays. Have you tried peer

revision with any success? What strategies have been useful?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)